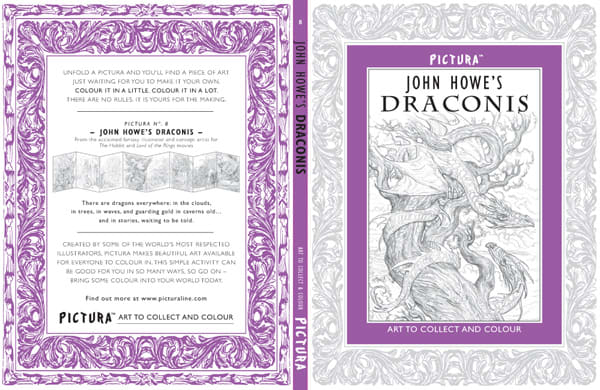

Arena Illustration are thrilled to be involved in the launch of a brand new range of books published by Templar.

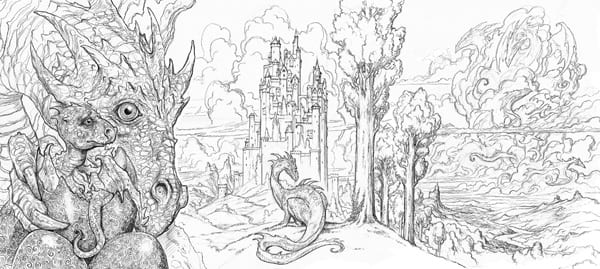

John Howe was asked to produce a panaromic drawing on the theme of dragons, which is a speciality of his after working with Smaug in New Zealand these past four years. John conceptualised the life cycle of dragons and where they might be found, he says:

“There are dragons everywhere. There are dragons in the clouds, in trees and waves, and dragons carved in stone, and guarding gold in caverns old, in stories waiting to be told…” and we see these brought to life through the eight panels in his DRACONIS

John was interviewed about his working methods by Pictura’s Art Director, Nghiem Ta…

How did you learn to draw?

I truly believe that everyone can draw, we all certainly had no trouble drawing when we were children! Most of us, though, un-learn how to draw at some point, usually around 8 or 10 years old, when other means of expression crowd it out, when abilities are momentarily left behind by expectations. I’m also convinced that the identical tools used to write or to draw – basically pencils, pens and paper – demand such a different focusing of attention, that adults who would wish to return to the spontaneity they possessed as children simply cannot, because the tools themselves set in motion reflexes of literacy and not of creativity.

Those who continue to draw throughout their lives retain that informal language of line and tone.

I’ve often imagined how hard it must be to teach art in public schools, it would be like having a class where each pupil spoke a different language. The role of the teacher would be to transmit a tongue of which all could learn the rudiments, mixing it with their own, learning a clarity of structure and communication without abandoning their own dialects. I was never able to take art classes in school except for the very last year of high school (art classes were already full of students with whom no one knew what to do but couldn’t send home before the bell, hardly future artists) where I was blessed with a wonderfully encouraging art teacher. Naturally, after that, I went to a real art school, and quite honestly, I’m still learning. Every day.

Where does your art usually begin: concept or line?

That is decidedly a chicken and egg question! A little of both, undoubtedly. I have the germ or the spark of an idea, but often very little, or more often, I know what subject I will be exploring, and the narrative into which it fits, and what the drawing should convey when it’s done. Then I generally start and let the pencil wander. Many artists have ideas more fully formed, and possess a graphic language that interprets the real work strongly, and for whom the act of drawing is getting it out of their heads and on to the page. I look at drawing as a kind of exchange, between the artist, the subject and the drawing itself. Sometimes, when the grip on the idea and on the pencil are light enough, a line will suddenly appear, and with it a new idea and a radical change of direction. Those moments are very exciting, and I wouldn’t want to miss them for the world. Additionally, the simple fact that to fill a large sheet of paper with lines from a tool sharpened to a fine point means that you have the time to reflect, for your initial idea to evolve. Finding a rhythm is crucial, just the right speed to remain loose and inventive, and to have time to allow serendipity to intervene.

What does colour mean to you?

Colour is a symphony, I really think of colour in musical terms (but then music is colours to me). I also have a confession to make, I NEVER do colour sketches. (The few times I have, at the request of the publisher, I have been miserable.) My only wish is to keep all of those possibilities open for as long as I can – density, contrast, depth, palette, all of those things need to develop on the final artwork. It’s a question of elbow room as well, I most enjoy the first few minutes, with a wide brush on very wet paper, when the potential image will either appear, or not. (I’ve learned to stop quickly if I’m unsure, stretch a new sheet and start again, rather than persuade myself it will be fine if I just keep at it.) Those initial couple of washes will establish the space within the image itself, while leaving the rest open to improvise.

Is learning to draw the same thing as learning to see?

The two go hand in hand. Drawing from life is almost a form of meditation, a suspension of time, where you can quite cease to exist, concentrating only on the triangular relationship you are creating with your subject and your drawing. Drawing something means truly looking at it. Translating a three-dimensional space or an object into two dimensions is an exercise in understanding. (The simple “tricks” that can seem hard to grasp are really quite simple and ultimately logical: perspective, the uses of shading, an understanding of light.) Nature doesn’t really have lines, it has forms, so each line is not just a line, it is a succession of lines delimiting contours, disappearing and reappearing. A line is never just a line. A sketchbook filled with drawings is the record of that growing knowledge and understanding. With each drawing you draw yourself closer to two things: understanding the nature of the world around you and depicting in patient graphite the worlds you have within. Like two mirrors placed face to face, the artist is somewhere in that infinity of reflection and counter-reflection.

Which medium do you normally work in?

I confess I’m a little old-fashioned in that respect, I prefer pencils and brushes and paints, though I can and do use Photoshop, principally for film work, as it is so much quicker. I generally do my sketches on a decent-sized sheet of paper, about 50 x 70 centimetres, or in a sketchbook. Once the drawing is satisfactory, I’ll stretch a large sheeting of heavier paper to paint on, either transferring the sketch with tracing paper, or just putting down a few lines to guide me into it. Many changes will happen along the way, before the artwork is finished. How do I know it is finished? Generally when I lose interest in it, which means (hopefully) that every question has been resolved and it is time to start the next one.

And you can read more from John Howe’s Chronicles about his work on Draconis

You can also find out more from Templar’s creative Director Amanda Wood as she explains the idea behind the series on the PICTURA website